this story is from November 14, 2020

‘Climate change is visible in Ladakh with glaciers losing ice — this impacts all of us’

Aerospace researcher Siddharth Pandey heads the Centre of Excellence in Astrobiology at Amity University, Mumbai, and is currently analysing the manifestations of global warming and climate change in Ladakh. Writing in Times Evoke Inspire, he discusses such climate impacts on the region — and how these will extend beyond Ladakh as well:

As a space researcher, my work involves exploring other worlds where life could exist. In one such project, we are researching regions on Earth that offer unique conditions supporting microbial life. Dry, cold, UV-exposed soils, ices and waters — Ladakh’s highaltitude desert regions, with their sand dune ponds, glaciers, salty lakes and hot springs, offer a range of ecosystems hosting microbial life.

To understand other planets — for instance, Mars’ present environmental conditions — we need to explore comparable scenarios. Ladakh helps to do that, since early Mars was a lot warmer and wetter than today, with comparable terrain.

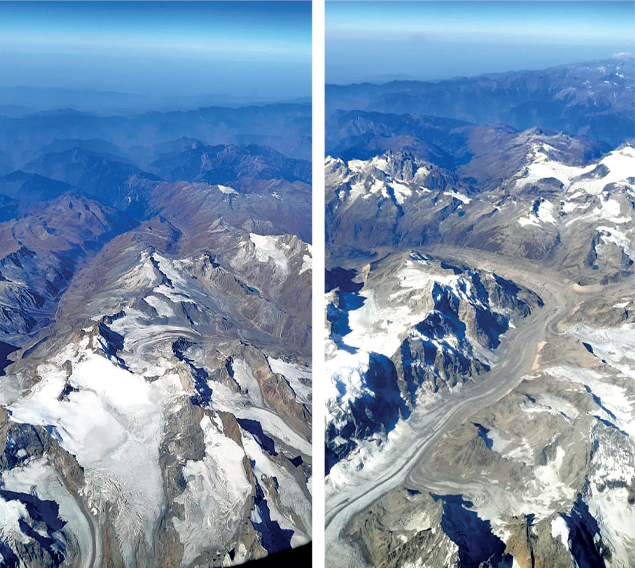

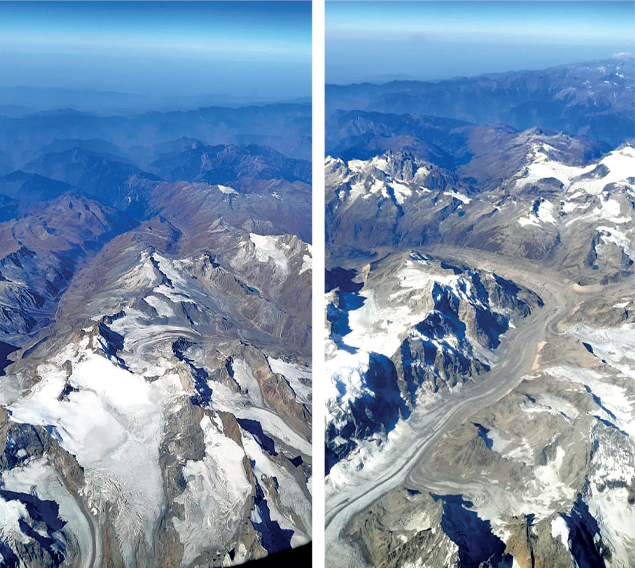

Dry Tides: The Bara Shigri glacier, bounded by Ladakh, is the longest in the Himachal Himalaya, storing some of north India’s largest freshwater reserves. Impacted by global warming, the glacier is receding, changing glacial streams (Photos: Siddharth Pandey)

Dry Tides: The Bara Shigri glacier, bounded by Ladakh, is the longest in the Himachal Himalaya, storing some of north India’s largest freshwater reserves. Impacted by global warming, the glacier is receding, changing glacial streams (Photos: Siddharth Pandey)

We are therefore studying how Ladakh’s landscape has evolved over time, the weathering of its terrain due to precipitation and winds, interspersed with the generation of microbial cultures. Ladakh’s topography is especially telling — being in a rain shadow region, it has seen relatively little weathering, with well-exposed rock surfaces revealing ancient events that shaped the land. There are fascinating stories of science here. But, on a recent research trip, I discovered another story unfolding in Ladakh.

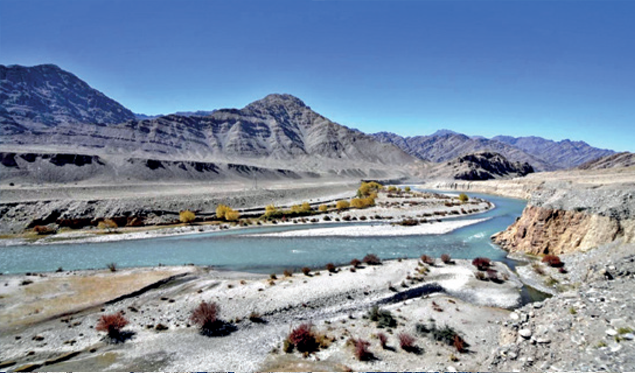

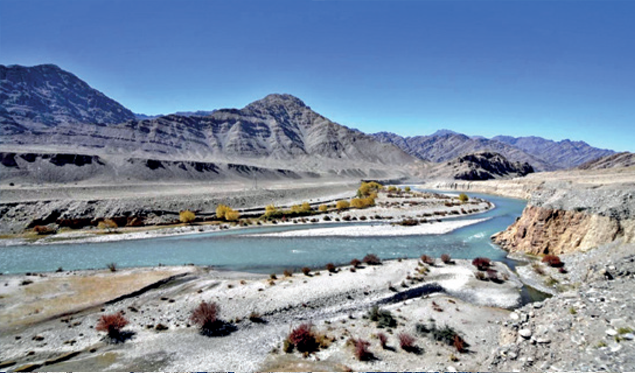

In Unknown Waters: Once, Ladakh’s Indus River sediments showed dynamic land movement as India joined Asia and the Himalayas rose. The historic river now faces the dangers of climate change

Travelling to the region, our team noted its famous crystal-blue lakes glistening in the sunlight. But we also noticed how several large glacial stream beds, once abundant, were now ice-free and even running dry. Over the last few decades, warmer air temperatures — caused by rising carbon emissions and intensifying greenhouse gases — have led to unusually high rates of ice melting and evaporation.

The Himalayas have an uneven terrain, due to which the effects of such climate change are enhanced. This means that while a glacial deposit could be melting in one area due to warmer winds, there could be a sudden downpour in another area, causing a glacial lake to overspill and a flash flood or a landslide to occur. Due to the rocky landscape, the excess water doesn’t get absorbed in the soil.

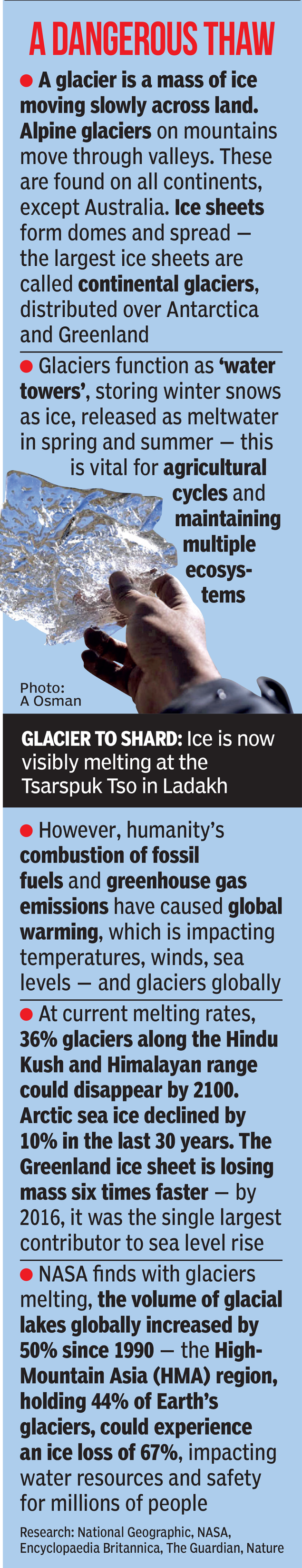

A Vital Lifeline: Glaciers from the Hindu Kush and Tian Shan to the eastern Himalayas provide water to rivers across central and south Asia

It rolls down, taking with it rubble, trees and whatever comes in its way, leading to disaster. Worryingly, the number of unusually high precipitation events has gone up by almost three times in the last decade itself. In the last 14 years, there have been frequent flash floods in Ladakh, one in 2010 causing losses of life and economic devastation.

Studies indicate that at this melt rate, over one-third of the Himalayan glaciers — the storehouses of major rivers — could be lost over the next 80 years. The resultant shortages of irrigation and drinking water will lead to mass relocations, potentially changing the fertile river plains of the north to desert-like areas, further impacting wind and weather patterns.

All the geospatial evidence I saw in Ladakh reaffirmed such an apocalyptic scenario occurring — unless we change our consumption and energy habits. The effects of not doing so show clearly in Ladakh — the cold, dry region, whose ecology, climate and fauna evolved over thousands of years, is now thrown entirely off-balance by urbanisation across Leh. The changes in local microclimate, in flowering and harvest seasons have befuddled farmers.

Alongside, fields are suffering as drying glaciers mean less irrigation water. Seeking water, some apple harvest belts have even had to move to higher altitudes. The dependence of farmers on commercial insecticides has also risen, leading to toxic materials appearing in soil, water and plants, unheard of just a generation ago. Burgeoning tourism has also had its own impacts.

Needing more water, Ladakhis, once sustained by glaciers, are now digging borewells, tapping into limited groundwater reserves to support tourism. Each summer, there are apparently three tourists for every local. As this number grows, so does the pressure on water — while water itself grows scarce.

I travelled from Leh to Tso Kar, a high-altitude wet basin. On the way up via Taglang La, a high pass, I saw dried-up glacial stream beds — and a completely icefree glacial top. Yet, locals remembered wading through knee-deep snow there just a few years ago. In the last year, very little snow had fallen.

At Tso Kar, once an important salt mining site where traders would gather to buy and sell salt, the drop in precipitation was visible — the dryer climate has led to the wondrous lake itself shrinking. This is alarming — a white salt deposit with green meadows, the rejuvenating Tso Kar sustains multiple plant and animal species as well as pastoralist nomadic groups.

How climate change will impact it now holds important consequences, for such local communities — and for people who live far away from Ladakh.

Times Evoke Inspire is a unique space for young readers to express their thoughts on the environment. Write in to:

timesevoke@timesgroup.com

As a space researcher, my work involves exploring other worlds where life could exist. In one such project, we are researching regions on Earth that offer unique conditions supporting microbial life. Dry, cold, UV-exposed soils, ices and waters — Ladakh’s highaltitude desert regions, with their sand dune ponds, glaciers, salty lakes and hot springs, offer a range of ecosystems hosting microbial life.

To understand other planets — for instance, Mars’ present environmental conditions — we need to explore comparable scenarios. Ladakh helps to do that, since early Mars was a lot warmer and wetter than today, with comparable terrain.

We are therefore studying how Ladakh’s landscape has evolved over time, the weathering of its terrain due to precipitation and winds, interspersed with the generation of microbial cultures. Ladakh’s topography is especially telling — being in a rain shadow region, it has seen relatively little weathering, with well-exposed rock surfaces revealing ancient events that shaped the land. There are fascinating stories of science here. But, on a recent research trip, I discovered another story unfolding in Ladakh.

In Unknown Waters: Once, Ladakh’s Indus River sediments showed dynamic land movement as India joined Asia and the Himalayas rose. The historic river now faces the dangers of climate change

Travelling to the region, our team noted its famous crystal-blue lakes glistening in the sunlight. But we also noticed how several large glacial stream beds, once abundant, were now ice-free and even running dry. Over the last few decades, warmer air temperatures — caused by rising carbon emissions and intensifying greenhouse gases — have led to unusually high rates of ice melting and evaporation.

The Himalayas have an uneven terrain, due to which the effects of such climate change are enhanced. This means that while a glacial deposit could be melting in one area due to warmer winds, there could be a sudden downpour in another area, causing a glacial lake to overspill and a flash flood or a landslide to occur. Due to the rocky landscape, the excess water doesn’t get absorbed in the soil.

A Vital Lifeline: Glaciers from the Hindu Kush and Tian Shan to the eastern Himalayas provide water to rivers across central and south Asia

It rolls down, taking with it rubble, trees and whatever comes in its way, leading to disaster. Worryingly, the number of unusually high precipitation events has gone up by almost three times in the last decade itself. In the last 14 years, there have been frequent flash floods in Ladakh, one in 2010 causing losses of life and economic devastation.

Studies indicate that at this melt rate, over one-third of the Himalayan glaciers — the storehouses of major rivers — could be lost over the next 80 years. The resultant shortages of irrigation and drinking water will lead to mass relocations, potentially changing the fertile river plains of the north to desert-like areas, further impacting wind and weather patterns.

All the geospatial evidence I saw in Ladakh reaffirmed such an apocalyptic scenario occurring — unless we change our consumption and energy habits. The effects of not doing so show clearly in Ladakh — the cold, dry region, whose ecology, climate and fauna evolved over thousands of years, is now thrown entirely off-balance by urbanisation across Leh. The changes in local microclimate, in flowering and harvest seasons have befuddled farmers.

Alongside, fields are suffering as drying glaciers mean less irrigation water. Seeking water, some apple harvest belts have even had to move to higher altitudes. The dependence of farmers on commercial insecticides has also risen, leading to toxic materials appearing in soil, water and plants, unheard of just a generation ago. Burgeoning tourism has also had its own impacts.

Needing more water, Ladakhis, once sustained by glaciers, are now digging borewells, tapping into limited groundwater reserves to support tourism. Each summer, there are apparently three tourists for every local. As this number grows, so does the pressure on water — while water itself grows scarce.

I travelled from Leh to Tso Kar, a high-altitude wet basin. On the way up via Taglang La, a high pass, I saw dried-up glacial stream beds — and a completely icefree glacial top. Yet, locals remembered wading through knee-deep snow there just a few years ago. In the last year, very little snow had fallen.

At Tso Kar, once an important salt mining site where traders would gather to buy and sell salt, the drop in precipitation was visible — the dryer climate has led to the wondrous lake itself shrinking. This is alarming — a white salt deposit with green meadows, the rejuvenating Tso Kar sustains multiple plant and animal species as well as pastoralist nomadic groups.

How climate change will impact it now holds important consequences, for such local communities — and for people who live far away from Ladakh.

Times Evoke Inspire is a unique space for young readers to express their thoughts on the environment. Write in to:

timesevoke@timesgroup.com

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE