We still have a ways to go toward our goal of $75,000! Support in-depth, unbiased journalism with a gift today.

For months the fragility of a vital air link endangered the health of people across rural Hawaii. The state is still trying to fix it.

For months the fragility of a vital air link endangered the health of people across rural Hawaii. The state is still trying to fix it.

Kristen Bettencourt-Pedro bolted awake at 2:30 a.m. and felt her water break. It was Feb. 6, almost five weeks before her baby’s due date.

In most circumstances, a woman in premature labor would rush by car to the nearest hospital, where medical staff would try to suppress labor or, if it couldn’t be stopped, get ready to deliver the baby.

But Bettencourt-Pedro, 34, lives on Molokai, where women with complicated pregnancies must board a plane in order to give birth under the care of a doctor.

The island’s lone hospital doesn’t perform cesarean sections and it prohibits vaginal births for mothers like Bettencourt-Pedro who have a prior history of C-sections. Women who give birth at the 15-bed Molokai General Hospital sign up for an unmedicated delivery with little access to medical interventions if things go awry.

It was just before 3 a.m. when Bettencourt-Pedro’s husband whisked her out of his truck and into the hospital’s fluorescent-lit birthing room. Medical staff ordered an air ambulance to transport her to Oahu while a nurse gave her drugs to slow or stop her body from trying to push the baby out.

Her contractions did not let up. And the state’s only air ambulance company had two other patients to move that morning before it could point a helicopter toward Molokai, just 26 miles southeast of the Honolulu medical hub.

Hours passed and, by dawn, still no air ambulance had arrived. The nurses tried to assure Bettencourt-Pedro that if worst came to worst she could push the baby out with the assistance of a midwife. But she remembers thinking she was going to die.

“It was scary,” she said. “I felt like I wasn’t being treated like a priority.”

Hawaii has one air ambulance provider: Hawaii Life Flight. The private company usually operates seven fixed-wing aircraft and a helicopter, responding to an average of five to eight calls a day.

But its capacity buckled last year on Dec. 15, when one of its planes crashed in the ocean, killing a pilot, flight nurse and paramedic. The company grounded its aircraft on every island except the Big Island, where a helicopter remained in service.

Hawaii needed an immediate back-up plan to fly people from rural neighbor islands to the state’s big city medical centers. Gov. Josh Green issued an emergency proclamation the day after the crash to allow the state to use local military aircraft and temporary mainland staffing to keep Hawaii’s medevac service running.

Stranded on Molokai in the midst of the stand-down, Bettencourt-Pedro felt helpless. In Honolulu, an obstetrician-gynecologist waited at The Queen’s Medical Center for her to arrive.

The sun had not yet risen when the doctor called Green and pleaded for help.

The governor, who worked as an emergency room doctor on the Big Island for years, was under no illusions: It was a dangerous situation.

If Bettencourt-Pedro remained on Molokai, the governor worried that she or her baby might die. He ordered the Army National Guard to send a Black Hawk helicopter to fetch her.

“That was the scariest moment of all of the period where our life flight capacity was limited,” Green said.

The Army National Guard does not have an on-call flight crew, however, and it would take at least an hour to mobilize a Black Hawk to Molokai. So hospital leaders negotiated a faster solution: Mokulele Airlines, the only commercial air carrier servicing Molokai, bumped two customers off its fully booked first flight of the day. Those seats went to Bettencourt-Pedro and an accompanying doctor.

It was nearly 9 a.m. when Mokulele’s nine-passenger plane landed at Honolulu’s Daniel K. Inouye International Airport after a 36-minute flight. Doubled over in labor pain, Bettencourt-Pedro could barely step down onto the tarmac. Paramedics strapped her on a gurney and wheeled her into an ambulance which took off toward Queen’s.

Harlyn Pedro arrived through an emergency C-section at 10:42 a.m. Her birth story is a traumatic portrait of a vital air link that for months fell short, endangering the health of people who live on the state’s outer islands.

Now it raises the question: Should state health regulators provide oversight to air ambulance companies?

After the December crash of the Hawaii Life Flight plane, it took investigators 26 days to find the wreckage submerged in 6,000 feet of water off East Maui. Hawaii Life Flight initiated what’s called a safety stand-down to give employees time to grieve, evaluate staff training needs and perform maintenance checks on its interisland planes, which were grounded.

It wasn’t immediately clear how long Hawaii Life Flight’s stand-down would last. The company told its employees they could return to work on their own terms.

The government’s intervention ensured that an aircraft picked up every patient who needed emergency medical care on another island. But the system struggled to handle case surges, forcing patients to sometimes wait hours for a flight. As the capacity shortage endured, the governor extended his emergency proclamation seven times, allowing it to expire on May 30 when Hawaii Life Flight’s capacity had finally stabilized. The company’s Molokai base remains closed, however, due to a ground crew staffing shortage and needed repair work.

“We allowed our crew a maximum time to return to service and it took a little longer that way,” said Speedy Bailey, regional director for American Medical Response, a partner firm. “I don’t disagree with what we did. I think that’s a long term benefit for everybody to come back when they’re ready.”

Looking back, Bailey said he would have enlisted more mainland flight crews to fill staffing holes during the company’s half-year of decimated capacity.

“Yes, people waited,” Bailey said. “There is that concern. But I don’t think anybody was left behind that needed to go.”

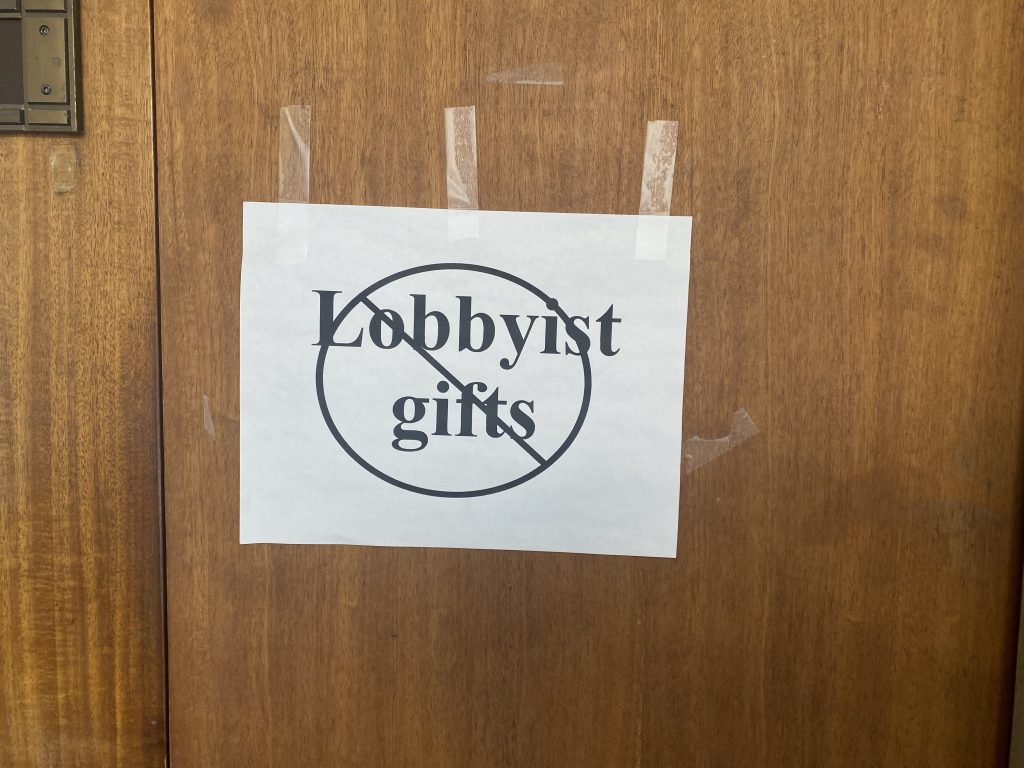

The Hawaii Department of Health regulates ambulances on the ground, not in the air. Private air ambulance companies are treated like airlines, with flight safety oversight provided by the Federal Aviation Administration. There is no regulatory body with an interest in ensuring that people in Hawaii have timely, equitable access to emergency air medical transport services.

If the events of the last six months have taught state officials anything it’s that relying on a blind trust in private market forces can have consequences when it comes to medical air transport. So health officials are examining whether the state can legally pursue a more active role in air ambulance oversight without running afoul of the FAA.

In one proposal, the state would forge contracts with one or more air ambulance providers to help ensure that emergency aircraft are stationed equitably throughout the islands.

It’s uncertain whether Hawaii taxpayers would be willing to subsidize a solution of this scale. It’s also unclear how many players the market can support. The risk of having an oversupply of providers in a state with an average of 2,500 air ambulance trips per year is that company profits could shrink and destabilize the industry.

Top reasons for air ambulance transport in Hawaii include cardiovascular problems, gastrointestinal symptoms and traumatic injury, state health officials say.

Officials are working to pinpoint the optimal number of aircraft the state needs. Although it’s reasonable to think most people would desire to have an air ambulance in short reach, there’s a significant cost to keeping an aircraft on deck, especially if it sits idle most of the time.

Hawaii Life Flight became the state’s lone air ambulance company in September when a second provider called LifeSave KuPono shut down. The company had operated for a decade with bases in Honolulu, Kahului and Hilo. Air Methods, the parent company, blamed the closure partly on inflation and low Medicaid reimbursements, which are sometimes so low in Hawaii as to barely cover the cost of care.

When Hawaii Life Flight absorbed the additional service volume, people sometimes had to wait longer for a medevac when multiple patients needed to be transported at once, Bailey said. In these situations, he said the company moved patients with the most severe medical needs first.

To attempt to meet the state’s medical aviation needs, Hawaii Life Flight usually has two planes stationed in Honolulu, two on the Big Island, one on Kauai, one on Maui and one on Molokai. There’s also a single-engine helicopter, which can’t make ocean crossings, posted on the Big Island.

The company is considering augmenting its fleet with a second helicopter, one that’s capable of interisland travel. This way, if the planes had to be grounded again, another aircraft would be at the ready to help maintain service.

Health officials have met with three other air ambulance providers to gauge their interest in starting up interisland programs in Hawaii. The state’s recent $72 million investment in Medicaid payments to health care providers has made the prospect more financially attractive for some companies.

Another legislative intervention would forge a state-county partnership to equip every county in the state with a twin-engine helicopter capable of making interisland crossings, something only Maui County can do today. The Maui medevac typically moves ill or injured patients between Maui, Molokai and Lanai. In the aftermath of the Hawaii Life Flight crash, it was deployed statewide.

Proponents say reproducing the Maui medevac model could give the state a sturdier backbone to hold its own during future disruptions. It might also prove beneficial during natural disasters. But it would take a bigger bite out of the taxpayer’s wallet, teeing up a potentially fraught legislative debate.

State officials are also exploring new ways to bolster neighbor island medical capacity to limit the need for medevac flights.

Encouraging doctors to take up practice in remote areas is challenging. But state lawmakers this session pushed the effort forward, setting aside $30 million for a loan repayment program for doctors, nurses and social workers.

Health care experts, however, say it costs less to transport ill or injured patients to Honolulu by air than to duplicate specialized services at smaller rural hospitals.

Molokai General Hospital has occasionally been approached by family physicians who’ve wanted to expand childbirth services on the island. There are roughly 100 babies born to Molokai women in an average year, but the hospital’s nurses only see about 30 births, said Molokai General Hospital President Jan Kalanihuia. Most expecting mothers give birth in Honolulu.

The hospital’s nurses simply don’t have enough experience to become proficient at spotting the signs of labor trouble, a crucial skill for doctor-supported births.

“With a physician, they count on nurses to labor sit their patient,” Kalanihuia said. “That could be 12 hours, and then they’re called in at the last second. We don’t have the nursing staff to support that model.”

For Bettencourt-Pedro, boarding a plane to access health care is an accepted way of life on a tiny, rural island with a longstanding doctor shortage. But it requires a degree of reliability from the aviation industry, most of all air ambulance providers.

Waiting five hours for a medevac was traumatizing, leading her to question whether she’ll try to have more children.

“My husband wants one more,” she said, “but I’m scared.”

Civil Beat’s coverage of Maui County is supported in part by grants from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation.

Civil Beat’s community health coverage is supported by the Atherton Family Foundation, Swayne Family Fund of Hawaii Community Foundation, the Cooke Foundation and Papa Ola Lokahi.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

More than 600,000 people read Civil Beat articles every month, but only 7,000 of those readers also donate to support the news they count on. That’s only 1% of readers!

If you are among the 99% of Civil Beat readers who haven’t made a donation before in support of our independent local journalism, you can change that today. A small donation makes a big impact. Give now!