Abstract

As the long-standing and ubiquitous racial inequities of the United States reached national attention, the public health community has witnessed the rise of “health equity tourism”. This phenomenon is the process of previously unengaged investigators pivoting into health equity research without developing the necessary scientific expertise for high-quality work. In this essay, we define the phenomenon and provide an explanation of the antecedent conditions that facilitated its development. We also describe the consequences of health equity tourism – namely, recapitulating systems of inequity within the academy and the dilution of a landscape carefully curated by scholars who have demonstrated sustained commitments to equity research as a primary scientific discipline and praxis. Lastly, we provide a set of principles that can guide novice equity researchers to becoming community members rather than mere tourists of health equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Defining health equity tourism

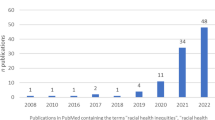

Diversity. Equity. Inclusion. Anti-Racism. Intersectionality. These are words with rich meanings, theoretical traditions, and scholarly legacies that are meant to inform the practice of pursuing cross-disciplinary justice, grassroots organizing, political advocacy, and scientific inquiry. Recently, they have also become buzzwords that have been shuffled into seemingly meaningless acronyms at healthcare institutions and research organizations. These same words are surfacing in requests for applications at major funding agencies and calls for papers from top health journals. The nascent fervor of soliciting equity-influenced work is linked to a magnification of racial injustice that has given a fresh lens for individuals who had not previously engaged in the work. This ideological shift has influenced funding streams, leaving academic researchers clamoring to adapt to these current shifts in the priorities of funding agencies and journals, and creating a predatory co-opting of scholarship that has been rigorously studied by equity scholars and social scientists for decades.

It is in this environment that we witness the evolution of the “health equity tourism” phenomena. We define “health equity tourism” as the practice of investigators—without prior experience or commitment to health equity research—parachuting into the field in response to timely and often temporary increases in public interest and resources. Health equity tourists fail in developing an enduring equity-focused research arms because they are reactionary rather than prospective. Tourists come to equity work because they recognize it is a viable option for research productivity and fiscal return rather than a long-standing commitment to health justice. Indeed, this type of academic tourism is often a definite departure from primary research focuses, framing “health justice” as a fruitful landscape waiting to be cultivated. Oftentimes, these scholars seek to “retrofit”, or adapt existing structures and research practices for health equity work, rather than build the necessary transformative infrastructure required for and sustainable health justice.

Antecedents to health equity tourism

A recent article in STAT news, brought attention to the issue of health equity tourism [1]. In that article, one of the common defenses used by tourists for pivoting into health equity research surfaced — an immediacy to address severe injustices. Notwithstanding good intent, it is impossible to separate the altruism buttressing this work from the perverse incentives that motivate academic publishing and eventual academic success. The capitalist society that researchers occupy concurrently influences academic job markets and tenure pipelines. In academic healthcare institutions and schools of public health, we are encouraged to generate large volumes of research published in high-impact journals to maintain our jobs and advance in our careers. This structure incentivizes scientists to latch onto current ‘hot topics” and makes it impossible to distinguish elements of altruism from career-benefiting extraction.

A similar phenomenon is seen in international health research where scholarship led by North American and European scientists extracts data from Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, or the Pacific Islands without meaningful scientific collaboration with authors from those regions. The omission of stakeholders from countries where such studies take place is not only parasitic, it is detrimental to the quality and validity of the science. However, when a manuscript includes data from low and middle-income countries, some journals and scholarly outlets may evaluate the inclusion of authors from these nations prior to publishing. The guideline of appraising work for global inclusion is generally accepted as a best practice in global health [2]. Imperfectly as it may be applied, this practice provides an instructive baseline to critically review the recent surge in scholarship branded as health equity research.

Historically, health equity research was an under-resourced field primarily comprised of people of color; individuals who shared ethnoracial backgrounds and lived experiences with the populations most harmed by systemic racism and healthcare discrimination. Now, as certain scholars (often white) pivot into this space, they do so without acquiring the necessary skills to produce high-quality work. They are individuals who are experts in other fields but novices in health equity research—whose hubris assumes that skills developed in other contexts are directly transferable to studying equity.

In fact, there is a robust scholarship detailing how methods commonly used in public health are not appropriate for studying systemic racism [3,4,5] and disciplines of methods research dedicated to adapting justice-based theoretical traditions (i.e. critical race theory and intersectionality) [6, 7]. “Community members” of the health justice environment, individuals who primarily focus on this work recognize, engage with, and advance this scholarship in the process of understanding barriers to health equity and addressing them. As such, the fundamentally different research practices of “tourists” have direct implications on the quality of the science and future of the field.

Ramifications of health equity tourism

Without an appreciation of these challenges, “tourists” are at risk of polluting the health equity landscape and riddling the academic record with ineffectual, and potentially harmful studies that mischaracterize root causes of health inequities and obfuscate potential solutions. For example, in the specific context of racial inequities for covid-19, several studies pursued genetic causes [8, 9] for the disproportionate mortality burden experienced by Black, Hispanic, and Latino/a/e, citizens in the United States. This is in stark opposition to two-well developed bodies of scientific literature; 1) that social inequities are among the main drivers of infectious disease burden [10, 11], and 2) that race is not a meaningful grouping for genetic similarity [12, 13]. Thankfully, and perhaps because of the recent interest in racial equity, strong studies have materialized that actually interrogate how social inequities cause disproportionate mortality burden in covid-19, including hospital system segregation [14], sequestration of racially oppressed groups into occupations with high transmission risk [15,16,17,18] and medical mistrust [19,20,21]. However, this speaks to another ramification of equity tourism, dilution. With the influx of tourists, “community members” of the equity space are at risk of being outnumbered and so are their work products. Coupled with whose voices tend to be amplified in public discourse, this leads to a landscape where laypeople and scholars alike are forced to sift through a muddied pool to identify evidence that can be appropriately used to catalyze equity advancement. While we hope that the current moment of racial equity becomes a sustained movement, if current fervor dies and tourists return home, pollution and dilution are destructive and costly. Community members will have to spend effort correcting poorly conceived studies before being able to move forward. Such work also contributes to the growing concern of research waste [22], expending resources on studies that sustain the academic publishing industry without improving health equity.

From tourist to community member, guiding principles and practices: (A specialist’s handbook)

It is our hope that the new emphasis on health equity research becomes a sustained commitment to achieving health justice. For that to happen, tourists must become community members and develop practices that foster a continued engagement with justice through science. To that end, we outline the following guiding principles.

Principle 1: Equity is fundamental

A community member framework is one that views equity as a fundamental goal of all scientific inquiry related to health, as opposed to an enterprise only tangentially related to their core research agenda. This framework requires that we proactively and continuously evaluate how elements of our practice and research may disproportionately affect oppressed communities. For example, in the case of a new planned intervention, the design phase must be scrutinized for how it will not only affect the average or “typical” patient, but also patients who don’t have routine access to care, lack economic resources [23], do not speak the dominant language [24], or are disabled. These individuals are frequently excluded from clinical trials, thereby obfuscating how potential interventions and recruitment strategies might perform among immigrant communities or “hard-to-reach” populations who represent various groups of historically-excluded peoples.

Science in healthcare is not neutral or apolitical; our research can either mitigate or contribute to systems of inequity. As an inaugural step towards adopting this framework view, novice equity researchers can consider the following questions to help understand the implications of their work. These questions will help investigators identify where their work might fall along this spectrum and strategize on how to shift it more toward justice:

Question 1: Who is represented in the study?

The reliance on “statistically significant” findings to determine the importance of our work generates an environment where the largest groups are regarded as most important. This assumption exists in opposition to centering the needs of historically-excluded groups—who are often underrepresented in data sources due to inequitable healthcare access and provider discrimination. In fact, the dominance of large groups in contemporary statistical methods and poor data quality due to systemic discrimination are cited as major challenges to fairness in prediction models, which are proliferating in clinical practice [25]. It is important to note that in many ways, this dominance is by design; in their book, “White Logic, White Methods,” Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva trace the eugenicist origins of statistical thinking and demonstrate how statistical methods, particularly those used to study race, perpetuate white supremacy [3]. Even in the common approach of identifying reference groups, we often frame white people as the “norm” or standard, implicitly circumscribing what is possible for other groups with a white lens. By applying “white logic”, we cause the relegation of smaller, historically-excluded groups to the limitations sections of studies, or in the case of Indigenous American populations, statistical genocide and the near erasure from the scientific record [26, 27]. Eliminating the practice of neglecting historically-excluded groups for the convenience of statistical properties is a minimum prerequisite to incorporating equity as a fundamental component of research. So, too is more inclusive recruitment and community-engagement strategies that strengthen our ability to conduct research with these groups.

Question 2: How can this work cause harm?

Research can cause harm in a variety of ways. Even when included in data for a study, published work on historically-excluded groups that is not conducted with or led by members from that group may contain spurious claims that perpetuate bias in science, thus promulgating harm that has already been caused by researchers. Second, when research is published, especially in the leading medical journals, the media and public tend to take the publication as “word” or “truth.” Not all that is published is correct, and some can be damaging. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there were several published examples (including in leading medical journals) that claimed a link between biology and pathophysiology of being Black to an increase in Covid-19 [8]. Scholarly journals have the responsibility to clearly articulate that racism is the mechanism by which racial categorizations have biological consequences. There are no pathophysiological differences between racial groups. Racial and ethnic inequities are caused by society (structural and institutional racism) and not directly by genes [9, 28,29,30]. Continuing to publish science that erroneously endorses a biological essentialist notion of health inequity localizes the point of intervention to individuals and historically-excluded groups, rather than identifying societal structures as the root cause which drives us farther from health justice [31].

Journals have the opportunity to play a critical role in mitigating the impact of health equity tourism by facilitating a process of reflection and requiring equity statements in reporting guidelines and article submissions. These statements should require authors to contend with, at minimum, the two questions raised above via a written statement detailing how exclusion and inclusion criteria used in the study might impact the generalizability of the findings with specific attention paid to historically-excluded groups such as disabled persons, undocumented groups, and indigenous populations, among others, as well as specific responses to anticipated erroneous and harmful interpretations of their results. There are already early precedents for such statements with the Journal of Hospital Medicine providing new author guidelines for the use of race and addressing racism in work submitted there [32].

Principle 2: Positionality as healthcare praxis

Dynamic health equity research engages an epistemological lens that is intrinsically tied to the researcher and bears an often overlooked nexus — who you are impacts the kind of science that you do. The rationales and origins of suppositions that undergird all academic research should be derived from the historically-excluded groups that are studied, not from a researcher whose implicit bias may generate assumptions that endanger rather than edify. Therefore, being a part of the community directly influences the quantitative and qualitative value of the research practiced. That is not to say that researchers outside particular racial, ethno-political, and gender identities should be barred from research within historically-excluded communities. However, these efforts must be pursuant to collaboration as a guide rather than ‘allyship’. In the social justice life-cycle, ‘allyship’ should be regarded as the most juvenile stage, requiring the deepening of one’s understanding through the use of books, mentorship, and private conversations.

Contextualized within health equity research, allyship is not sufficient. In order to truly augment the voices and improve the lives of historically-excluded communities, a reactive phase (accomplice) and proactive phase (co-conspirator) is critical [33]. Through a sustained recognition of their own privilege and the structures they inhabit, accomplices work to dismantle systems of oppression by tapping into their own privilege and “interrogating institutional bias”. While the first two phases center the researcher’s growing education and self-identification, a co-conspirator is a label assigned through extended community practice by the individuals being served. Co-conspiratorship is a proactive phase because it returns the hierarchical power of justice back to communities, equips community-members with the tools needed for their own liberation, and reunites philosophical and theoretical “truths” of research with the quantitative data and lived experiences of these communities.

Principle 3: Collaboration

Just as no single discipline independently handles all aspects of patient care, a research team concerning health and health equity should include a transdisciplinary assortment of professionals. The voices of clinicians, mental health professionals, social workers, and community advocates all merit inclusion in the collaborative work of health equity research. However, we need to resist the tendency to tokenize health equity researchers, adding them as commodities that act primarily as decorative baubles for optics, but instead empower them to lead efforts and rebuild systems.

An investigation of how we define and practice collaboration in academic and healthcare settings is desperately needed. Dr. Caren Cooper astutely reveals that most of us who have had the privilege of existing in scientific spaces as academics and healthcare professionals have been doing so “behind closed doors,” where only a privileged few get to be a part of the creation and expansion of human knowledge [34]. This widespread tendency for “closed-door” science excludes the most important scientific partners: the public. When collaboration occurs within the confinement of the academy and those they have historically deemed worthy of participation, inequity flourishes. The historical professionalization of science prompted the transfer of knowledge creation from the public domain to the academy [35]. Most methods of collaboration in the academy and healthcare would have us believe that individuals without specific credentials or positions do not meet the qualifications to meaningfully contribute to research. However, individuals from historically-excluded groups realize that value and expertise can also be sourced from lived experience, community, traditional knowledge, and positionality. New methods of collaboration beget a process that is slower and de-individualized and fundamentally de-centers the researcher.

Precedents for models of collaboration that redistribute power and move away from solely researching populations to researching and collaborating with them exist. Citizen Science is a form of participatory research involving the engagement of the public (non-professional “citizen” scientists) in scientific inquiry ranging from data collection and analysis to research question formulation and goal setting [36]. A citizen science approach to collaboration offers an avenue to redefine how we collaborate, what constitutes expertise, and who can be involved in knowledge creation [37]. Open and public science methods, make room for traditional, indigenous, and population-specific knowledge and co-creation with groups whose value has been historically minimized or erased [38]. According to the Ten Principles of citizen science, developed by the European citizen science association, proper credit and acknowledgment of the contributions of citizen scientists are essential [39]. Collaboration that is separated from equity will become increasingly insufficient as we hope to make equity a reality for more people.

Principle 4: Sustainability in urgency

When tourists enter a space with an emphasis on “quick action”, mistakes are often made. The reality is, many of the observed inequities are long-standing (e.g., Black infant and maternal mortality) or acute shocks to an already unjust system (Covid-19 racial mortality burden). In truth, few studies have immediate impact on health equity and often become part of a cumulative evidence base used to motivate policy changes. There are no research emergencies, and such expediency can result in deficits-based science that pathologizes communities rather than redistributing power and resources. “Rushing in” frames populations made vulnerable by systemic discrimination as incapable of directing their own liberation, suggesting that they need to be saved while actively avoiding the eradication of the very structures, systems, and practices that hoards the power, resources, and opportunities from these communities.

Secondly, there is an expected pacing in research that is not conducive to the time investment necessary for equity work. This pacing benefits the systems that reward productivity over impact and transformation. Equity work requires time investment, the idea that collaborating with community members and individuals from historically-excluded backgrounds is inconvenient due to urgency localizes the “knowledge and power” with the investigator and neglects the autonomy, resilience, and value of the communities in question. Sustainability is a critical component of equity work that must be embedded in the practice at all stages of the research interaction. The tourist sense of urgency increases the likelihood of overlooking the importance of sustainability strategies, tactics, and metrics. There is no liberation without sustainability, equity work involves actively challenging, transforming, and eradicating existing power structures with the goal of emancipation. The emancipatory research paradigm is embedded in this practice; it is in this framing that we recognize that interpretive and positivist paradigm privileges the researcher in the exchange of power. Equity work must utilize the emancipatory paradigm to relinquish power and resources to communities’ members. Sustainability is liberation; liberation is true equity, and, as we have outlined, equity work is a practice that requires time investment and a transforming of the social relations of research production [40].

Conclusion

Health equity research is an arduous undertaking even for experienced scholars who are committed to the field. In a frighteningly short time, we have witnessed the rise of equity tourism and pollution of the scientific record with subpar and potentially dangerous work. If the recent interest in equity work fails to become a sustained commitment from the academy, at best community members of the health equity landscape will be forced to de-toxify the record and at worst mitigate the harm left in the wake of tourist departure. In health we need to understand the boundaries and limitations of scientific expertise, and recognize the unique theoretical and ethical considerations that are intrinsic to high-quality health equity research. Through this piece, we model the power of team-based thought leadership and idea articulation among purposively aligned multidisciplinary scholars.

Equity tourism is precipitated by the antiquated capitalist environment in which knowledge production occurs. Therefore, the guiding principles and practices we offer are a stopgap solution until we completely dismantle and rebuild the infrastructure of academic research, publishing, and promotion. Authentic health equity researchers have always understood the need for emancipatory methods that include community partnership as a foil to extractive researchers who are opportunistic in their approaches without regard for the people impacted by the research. It is unfortunate that our time must be spent surveilling our fields for harmful work of tourists which remains a distraction from the real work we all seek to be doing while being acknowledged for the expertise we hold and represent. We ask our colleagues to do better.

References

McFarling UL. How white scholars are colonizing research on health disparities. STAT News. Published September 23, 2021. Accessed 24 Oct 2021. https://www.statnews.com/2021/09/23/health-equity-tourists-white-scholars-colonizing-health-disparities-research/

Health TLG. Closing the door on parachutes and parasites. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(6):e593. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30239-0

Zuberi T, Bonilla-Silva E. White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 2008.

Bowleg L. The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House: Ten Critical Lessons for Black and Other Health Equity Researchers of Color. Health Educ Behav. 2021 Jun;48(3):237–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/10901981211007402

Hardeman RR, Karbeah J. Examining racism in health services research: A disciplinary self-critique. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(S2):777–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13558

Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: Praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1390–1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030

Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022

Bunyavanich S, Grant C, Vicencio A. Racial/Ethnic Variation in Nasal Gene Expression of Transmembrane Serine Protease 2 (TMPRSS2). JAMA. 2020;324(15):1567–1568. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.17386

Severe Covid-19 GWAS Group. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1522–1534. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2020283

Asabor EN, Vermund SH. Confronting structural racism in the prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):e3531–e3535. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1763

Freudenberg N, Fahs M, Galea S, Greenberg A. The impact of New York City’s 1975 fiscal crisis on the tuberculosis, HIV, and homicide syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):424–434. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.063511

Witherspoon DJ, Wooding S, Rogers AR, et al. Genetic similarities within and between human populations. Genetics. 2007;176(1):351–359. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.106.067355

Roberts D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century. New Press/ORIM. 2011.

Asch DA, Islam MN, Sheils NE, et al. Patient and hospital factors associated with differences in mortality rates among black and white US medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112842. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12842

Hawkins D. Differential occupational risk for COVID-19 and other infection exposure according to race and ethnicity. Am J Ind Med. 2020;63(9):817–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23145

Waltenburg MA. Update: COVID-19 Among workers in meat and poultry processing facilities ― United States, April–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6927e2

Bui DP. Racial and Ethnic Disparities Among COVID-19 Cases in workplace outbreaks by industry sector — Utah, March 6–June 5, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e3

Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(9):e475–e483. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X

Rusoja EA, Thomas BA. The COVID-19 pandemic, Black mistrust, and a path forward. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100868

Bogart LM, Ojikutu BO, Tyagi K, et al. COVID-19 Related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among black americans living with HIV. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(2):200–207. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002570

Ash MJ, Berkley-Patton J, Christensen K, et al. Predictors of medical mistrust among urban youth of color during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(8):1626–1634. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibab061

Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Research waste is still a scandal—an essay by Paul Glasziou and Iain Chalmers. BMJ. 2018;363:k4645. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k4645

Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Chamberland S, et al. Disparities in initiation of direct-acting antiviral agents for hepatitis c virus infection in an insured population. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(4):452–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354918772059

Egleston BL, Pedraza O, Wong YN, et al. Characteristics of clinical trials that require participants to be fluent in English. Clin Trials. 2015;12(6):618–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774515592881

Gianfrancesco MA, Tamang S, Yazdany J, Schmajuk G. Potential biases in machine learning algorithms using electronic health record data. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1544–1547. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3763

Secaira M. Abigail Echo-Hawk on the art and science of decolonizing data | Crosscut. Accessed 3 Nov 2021. https://crosscut.com/2019/05/abigail-echo-hawk-art-and-science-decolonizing-data

Huyser KR, Horse AJY, Kuhlemeier AA, Huyser MR. COVID-19 Pandemic and indigenous representation in public health data. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(S3):S208–S214. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306415

Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466–2467. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8598

Dorn A van, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395(10232):1243–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X

Wallis C. Why Racism, Not Race, Is a risk factor for dying of COVID-19. Scientific American. Accessed 15 Nov 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-racism-not-race-is-a-risk-factor-for-dying-of-covid-191/

Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35:80. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626958

Andrews AL, Ndidi N, Shah SS. New author guidelines for addressing race and racism in the journal of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(4):E1–E4. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3598

Jana DT. The differences between allies, accomplices & co-conspirators may surprise you. Medium. Published 8 Feb 2021. Accessed 5 Nov 2021. https://aninjusticemag.com/the-differences-between-allies-accomplices-co-conspirators-may-surprise-you-d3fc7fe29c

Citizen Science: Everybody Counts | Caren Cooper | TEDxGreensboro - YouTube. Accessed 6 Nov 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7cQHSqfSzI

Mahr D, Göbel C, Irwin A, Vohland K. Watching or being watched-enhancing productive discussion between the citizen sciences, the social sciences and the humanities. In UCL Press. 2018.

About CitizenScience.gov | CitizenScience.gov. Accessed 6 Nov 2021. https://www.citizenscience.gov/about/

Hinckson E, Schneider M, Winter SJ, et al. Citizen science applied to building healthier community environments: advancing the field through shared construct and measurement development. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):1–13.

Tengö M, Austin BJ, Danielsen F, Fernández-Llamazares Á. Creating synergies between citizen science and indigenous and local knowledge. BioScience. 2021;71(5):503–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biab023

Robinson LD, Cawthray JL, West SE, Bonn A, Ansine J. Ten principles of citizen science. In: Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. UCL Press. 2018:27–40.

Oliver M. Changing the social relations of research production? Disabil Handicap Soc. 1992;7(2):101–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02674649266780141

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Health Policy

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lett, E., Adekunle, D., McMurray, P. et al. Health Equity Tourism: Ravaging the Justice Landscape. J Med Syst 46, 17 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-022-01803-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-022-01803-5