It seems that a lot of us “miss the rains down in Africa”. Of all the strange sociological consequences of Covid-19, few would have predicted that one would be a renaissance in certain songs from our dim and distant past.

But Toto’s 1982 soft rock classic Africa is one of several tracks from yesteryear that have enjoyed a surge in popularity during lockdown.

While the top 200 list on the Spotify music streaming service is crammed full of artists anyone over the age of 25 probably hasn’t heard of, new research shows some older artists have come to the fore since the UK imposed restrictions back in March.

Dr Timothy Yu-Cheong Yeung, of the Centre for Legal Theory and Empirical Jurisprudence at the University of Leuven, Belgium, in Brussels, analysed data from almost 17 trillion songs played on Spotify in six European countries – Sweden, the UK, Spain, France, Belgium and Italy – and found lockdown “significantly changed music consumption” in terms of listeners’ feelings of nostalgia.

The research, published in the journal Covid Economics from the Centre for Economic Policy Research, shows that the nostalgia effect peaked roughly 60 days after lockdown policies were introduced in each country.

Yeung said his research had started out as a joke with friends. “I have been in Belgium during the whole lockdown period. Life is boring and the only comfort is to revisit my 90s favourites, from Radiohead and Pulp to Blur. And I also saw many similar comments on YouTube saying that they felt nostalgic. I chatted with friends and joked that I could write an academic article out of it. Evidence supports I’m not wrong.”

Few of Yeung’s Britpop favourites enjoyed a renaissance, however. Most of the songs that did well were from the 1980s or even earlier.

Toto’s Africa made Spotify’s UK daily top 200 only 12 times in both February and March. But this had risen to 28 times by May. This increase was eclipsed by the huge surge in popularity of Electric Light Orchestra’s 1977 classic Mr Blue Sky, which charted only once in January but peaked at 31 times in May. Another 1977 hit, Fleetwood Mac’s Go Your Own Way – one of several tracks by the band to make the top 200 – enjoyed similar success while Here Comes the Sun by the Beatles from 1969, which had never been in the UK’s top 200 in the months leading up to Covid-19, made it into the listings 19 times in May and was played up to 63,000 times a day.

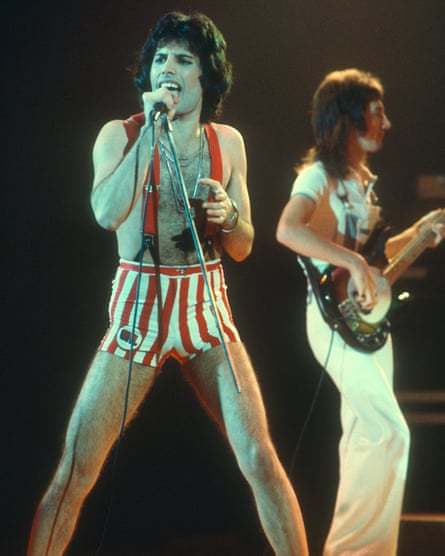

Other old songs that benefited from the nostalgia trend include Oasis’s Wonderwall and Don’t Look Back in Anger from 1995, Queen’s Don’t Stop Me Now from 1979 and Snow Patrol’s Chasing Cars from 2006. Elton John’s Tiny Dancer from 1971 and Bryan Adams’s 1985 hit Summer of ’69 also crept into the UK top 200 during lockdown. On Friday, the reissue of the Rolling Stones’ 1973 album Goat’s Head Soup went to No 1 in the UK album charts.

Yeung classed songs as nostalgic if they were older than three years and the model was adjusted for the effect of older users who had more time on their hands during lockdown.

Previous studies have confirmed that a crisis can affect consumption patterns, Yeung said, pointing out that they have shown that women tend to buy more beauty products during recessions (known as the “lipstick effect”). In this respect, economists believe music can be viewed as just another product to be consumed. And, while other studies have shown that music consumption actually fell during the initial phase of lockdown, it bounced back quite quickly.

Yeung’s paper suggests it might have tracked people’s shifting reactions to the new restrictions. It notes: “The lockdown involved many exceptional orders that limit individuals’ liberty and affect employment and usual social interactions. These changes might have caused ill emotions and people dived into nostalgic music to escape the reality, even if the virus had not caused their or their close relatives’ health any harms. Demand for nostalgia grew with frustration as the lockdown remained in place and such a change in behaviour was gradual but did not react closely to the change of the severity of the pandemic.”

But why the vogue for older songs? Yeung has his own theory. “Negative emotions are various but they are similar in one dimension, which is it hurts and leads people to react, to amend, to try to counter the negative feelings. One possible way to recover – or to generate positive utility – is to seek nostalgia that reminds people of the good old days.”

Some of the songs that have enjoyed a new surge in popularity are clearly optimistic, but Yeung said the overall picture was complex. “Many people claim that melancholic songs help them cope with difficult times while some prefer danceable and poppy songs to forget the present. The result up to now is quite mixed. Empowering songs seem to be the favourites during the lockdown.”

Yeung’s research might sound esoteric but it does carry potential policy implications. It suggests: “Care centres, hospitals, stores and any places where music could be played publicly should consider the positive effects of playing nostalgic music as a response to the adverse effects of the pandemic.”