How Indiana Jones Actually Changed Archaeology

Blockbuster film series led to spike in archaeology courses, careers.

Don your leather jacket and fedora, strap on a satchel, and get that bullwhip cracking: It’s time to explore the mythical intersection of Hollywood fantasy and real-world discovery.

Three decades ago, Indiana Jones’s swashbuckling brand of archaeology inspired a generation of moviegoers. Now a new exhibit at the National Geographic Museum pays homage to the actual artifacts and archaeologists that inspired Indy’s creation.

Opening Thursday, “Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology” brings together movie memorabilia from LucasFilm Ltd., ancient objects from the Penn Museum, and historical materials from the National Geographic Society archives.

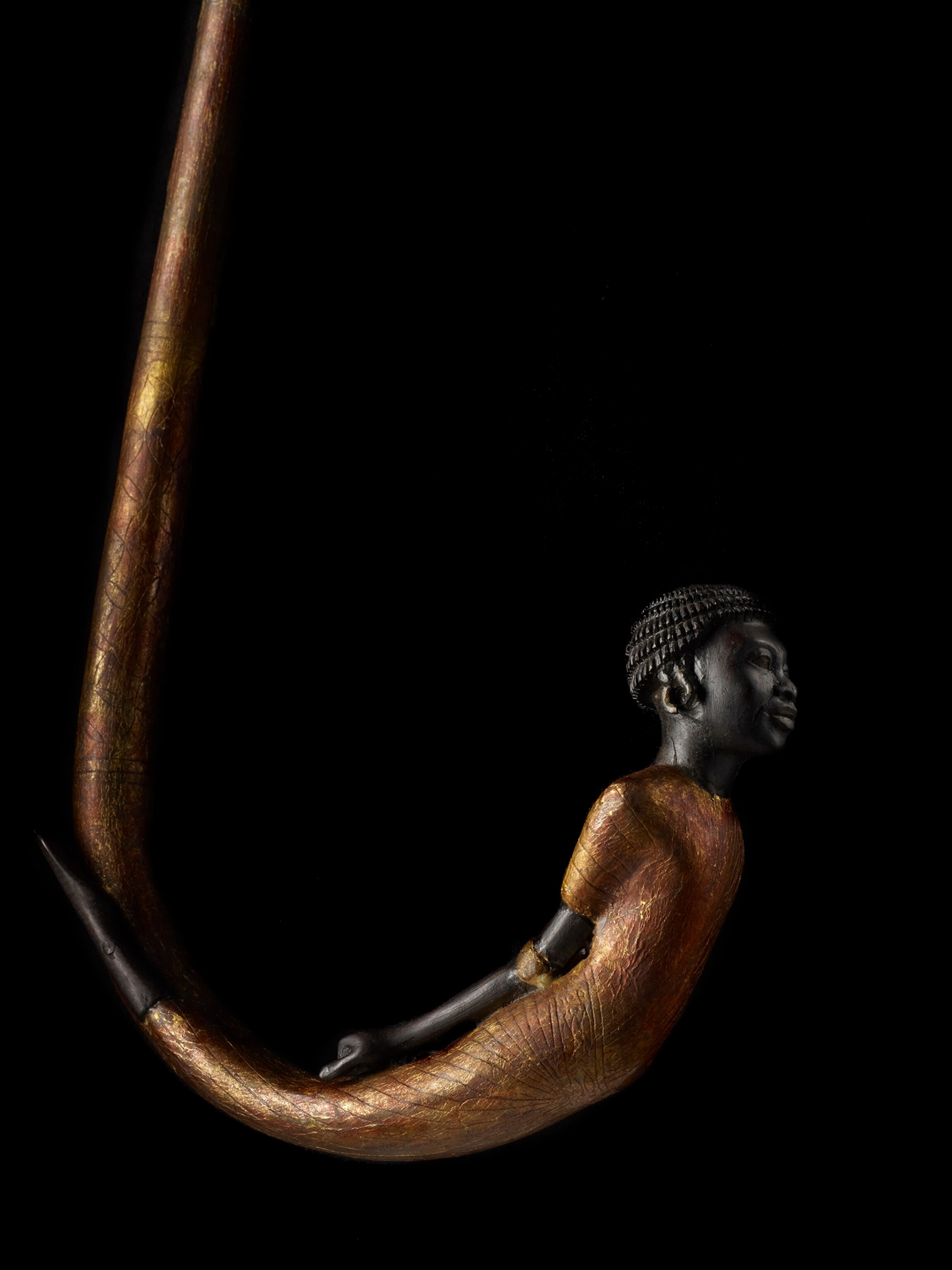

Some of the artifacts are real, including the world’s oldest map (a cuneiform tablet showing the city of Nippur), pieces of 5,000-year-old Mesopotamian jewelry, and iconographic clay pots that helped unlock the mystery of the Nazca Lines.

Indiana Jones’s swashbuckling brand of archaeology inspired a generation of moviegoers.

Other objects—like the Sankara Stones, the Cross of Coronado, and a Chachapoyan fertility idol—were imagined for the movies. And then there are some that hover in the fact-or-fiction netherworld: the Holy Grail, for instance, and the Ark of the Covenant. (Since no actual Ark has ever been found, the one built for Raiders of the Lost Ark, on display here, has become the iconic image—a case of life imitating art.)

The point, says exhibit curator Fred Hiebert, a renowned archaeological fellow at National Geographic, is “to show how much these films have broadened the scope of archaeology and made the field more relevant—and exciting—to people everywhere.”

The Power of Four

Stroll through the immersive, interactive exhibit and you soon realize that four is the magic number.

Clips from the four Indiana Jones films—Raiders, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull—flicker on the walls. At the same time, you move through four themed sections, each based on the work real archaeologists do: quest, discovery, investigation, and interpretation.

Hollywood is well represented here. Harrison Ford’s recorded voice greets visitors as they enter. Two-dimensional sketches and set designs adorn the walls. And items of clothing worn by Karen Allen, Kate Capshaw, and Sean Connery beckon inside glass cases.

But real archaeology gets equal billing. Side by side with the props, costumes, and storyboards are lessons on stratigraphy and archaeological technology such as Lidar, pre-Columbian drawings by the English illustrator Annie Hunter, and field photos of the Mayan scholar Tatiana Proskouriakoff.

George Lucas modeled Indiana Jones after the heroes in 1930s matinée serials. But he was also inspired by real archaeologists like Hiram Bingham, Roy Chapman Andrews, and Sir Leonard Woolley.

George Lucas created Indiana Jones as a tribute to the action heroes of his favorite 1930s matinée serials. But he was equally inspired by real 20th-century archaeologists like Hiram Bingham (National Geographic’s first archaeological grantee), Roy Chapman Andrews, and Sir Leonard Woolley. Their exotic exploits—finding lost cities, discovering treasure, deciphering hieroglyphics—captured the public imagination.

Decades later, they inspired four films that braid pop culture and Hollywood magic with world history and archaeological science.

The Archaeology of Influence

“These films introduced so many people to archaeology,” says Hiebert. “We can document their impact statistically, based on the number of archaeology students before and after the first film. Some of the best archaeologists in the world today say Indiana Jones was what sparked their initial interest. That’s a great legacy for George Lucas—and for the relationship between popular media and science.”

John Rhys-Davies agrees.

Reached by email, the Welsh actor who played the Egyptian excavator Sallah—Indy’s burly, bearded sidekick in two of the films—writes, “I must have met at least 150 or 160 full professors, lecturers, practising archaeologists who have come up to me to say their first interest in archaeology began when they saw Raiders of the Lost Ark. That's not a bad legacy for any film!”

'Cultural artifacts need to stay in the place where they come from,' says National Geographic archaeological fellow Fredrik Hiebert. 'I hope this exhibit will put a spotlight on cultural heritage, looting, and loss of heritage.'

Life Vs. Art

Of course, says Hiebert, real archaeology happens in the real world.

“Unlike Indiana Jones,” he says, “I actually have to write research proposals and reports, take field notes and photographs. The big difference [between movies and reality] is that massive parts of the archaeological job—from creating and testing a hypothesis to raising money to getting permits and tools—are glossed over by Hollywood.”

Davies is aware of those discrepancies, and best practices.

“The films represent the ‘loot and scoot’ school of archaeology,” he writes. “Not at all the way it's really done! The painstaking recording and documentation of every phase of a dig tells us as much as the object retrieved. What the films do, though, is create that sense of awe and mystery that comes when we try to uncover the past.”

Although Indiana Jones seeks “fortune and glory,” he understands that the objects of his desire belong in a museum.

“And that’s exactly the message National Geographic has,” says Hiebert. “Cultural artifacts need to stay in the place where they come from. Where they belong. I hope this exhibit will put a spotlight on cultural heritage, looting, and loss of heritage—a worldwide phenomenon going on now in Iraq and Syria and Peru and Egypt.”

He also notes a less serious offense.

“Hollywood has a very vivid imagination when it comes to booby traps,” Hiebert says with a grin. “Indy encounters them everywhere. But I don’t think any professional archaeologist has come across a booby-trapped site yet.”

The movies do mirror reality in at least one way, Hiebert says.

“I’ve worked on five different continents, and every place I’ve worked—whether it’s underwater, in the sands of Turkmenistan, or in the jungles of Honduras—I always find dens of snakes. Always.”

13 Photos: The Wonder of Archaeology

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

Environment

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

History & Culture

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

Science

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

- What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?

- Oral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuriesOral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuries

- How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

- Science

How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

Travel

- How to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplingsHow to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplings

- The best long-distance Alpine hike you've never heard ofThe best long-distance Alpine hike you've never heard of

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- How to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake ComoHow to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake Como

- Going on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboardGoing on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboard